Separate & Unequal (part 3)

Separate and UNequal Pt. 3

After reading part 3, I was intrigued by the idea that positive resolutions are essentially always a part of the process after disagreement or failure in change. I decided to look into what older policies are still intact in todays education system and which are simply masked to seem ethical and appealing to the minority population. After digging I found a documentary made in 2014, about the Baton Rouge school district in Louisiana, and how parents are fighting to segregate schools in their communities, essentially blaming the students who are to white for the educational shortcomings of other students. They think that the integrating of races in school is more of a risk than a step forward.

Below is the documentary trailer I found! Check it out.

In my own opinion, I think this would be like taking 10 steps back after having come so far from segregated schools. Growing up in one of the most diverse cities in the country, I am beyond thankful for the diversity in my own school system, as it has opened my own eyes, and many of those around me to the different cultural habits of the other students around us and allows room for respect and camaraderie with people even though their cultures and routines are complete opposites to yours. Integrated schools have allowed help in reducing disparities in access to well-maintained facilities, highly qualified teachers, challenging courses, and private and public funding. Diverse classrooms prepare students to succeed in a global economy. The conversation of segregation and education wouldn't be complete without mentioning Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. In this milestone decision, the Supreme Court ruled that separating children in public schools on the basis of race was unconstitutional. It signaled the end of legalized racial segregation in the schools of the United States, overruling the "separate but equal" principle set forth in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case.

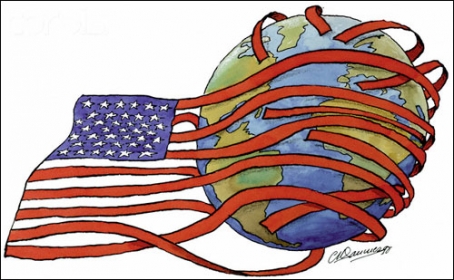

Few in the country, black or white, understood in 1954 that racial segregation was merely a symptom, not the disease; that the real sickness is that our society in all its manifestations is geared to the maintenance of white superiority.

Judge Carter argued that the changes in policy and practice that emerged from Brown and other civil rights legislation addressed superficial symptoms, leaving the disease of White supremacy/racism embedded in U.S. institutions.

Comments

Post a Comment